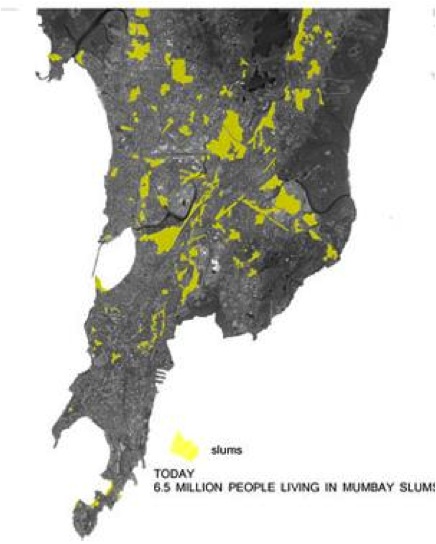

Despite being the financial capital of India, over half of Mumbai’s population live in slum settlements (World Bank 2006).

Distribution of slums in Mumbai (Dutt 2014)

A rapidly growing population coupled with limited resources has led to the challenges seen by the government today to provide its people with basic services, especially adequate housing and related infrastructure. Many houses in these slums do not have doors, 58% of the community does not have electricity and 78% of community toilets lack water supply (Guardian 2017).

Slums in Mumbai (Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo)

“The World Bank funded Slum Sanitation Project (SSP) has been working to address slum sanitation problems in Mumbai and has helped over 400,000 people living in Mumbai’s slums. “It was a demand-responsive initiative that incorporated a participatory approach to offer incentives to multiple stakeholders to work together to deliver community sanitation.” Throughout the period of 1996-2005, the SSP constructed about 330 community toilet blocks (CTBs) with more than 5,100 toilet seats. They were then handed back to the communities to use and maintain (World Bank 2006).

The poorest of the poor pay 10m rupees (£120,000) per day to use community toilets, according to the Observer Research Foundation, yet the Mumbai SSP estimates that 1 in 20 people are forced to relieve themselves in open areas due to lack of toilet facilities. In February 2017, there were reports in the Guardian and the Times of India of people dying from falling into the poorly maintained septic tanks – 7 people over the course of around 3 months.

Although Mumbai has a centralised chlorinated water supply, it does not run through most slums. The government’s reasoning for this is that some of these slums have been built illegally on government-owned land. To combat this, the Bombay High Court issued a ruling in 2014 that required Mumbai’s government to extend its water supply to those living in slums but this new policy excludes slums built on government-owned land. The water supplied to this type of slum is not required to be at the same quality or price as that to ‘formally housed’ citizens and the supply can be removed once residents are rehoused (WHO 2015).

In developing countries like India, is it possible to assume that a government does not value its poor citizens as much as its wealthy? Is economic development a greater governmental issue than the health of its population? Do poor people not deserve access to basic human rights?

Perhaps this is not fair to say, as demonstrated in Patel’s 2012 paper in which the government in Mumbai provided the initial capital for a community-managed public toilet programme left the responsibility of maintenance costs to the community. For citizens of developed countries (such as myself), public toilets would not be considered a solution for sanitation issues, but it may be important to take a different perspective as many of these toilets were designed by women living in these slums, so if they’re happy with the solution, should we be too?

References:

Koppikar, S., 2017. Death-trap toilets: the hidden dangers of Mumbai’s poorest slums. The Guardian, 27 February. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2017/feb/27/death-trap-toilets-mumbai-india-slums

The Mumbai Slum Sanitation Project, 2006. Partnering with Slum Communities for Sustainable Sanitation in a Megalopolis. The World Bank.

Patel, S., Baptist, C., and D’Cruz, C., 2012. Knowledge is power – informal communities assert their right to the city through SDI and community-led enumerations. Environment & Urbanization, 24 (1), 13-26

Subbaraman, R. and Murthy, S. L., 2015. The right to water in the slums of Mumbai, India. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2015; 93:815-816.

Pingback: Mumbai: Water Ration, No Compassion | Cityness

Pingback: Mumbai: What a waste! | Cityness